Wayfinding at the Royal Ontario Museum

OVERVIEW

The Royal Ontario Museum underwent a major renovation in 2007 connecting its historic building with the Daniel Libeskind Crystal. The new layout made it difficult for visitors to find their way around the museum as the floors did not connect seamlessly and the spaces were defined by vastly different architectural styles. I worked with the wayfinding lead to develop a plan to make navigating the buildings easier. I led the user testing, gathered directional information and helped design the wayfinding system.

THE NAVIGATION PROBLEM

We spoke with visitor services and staff in the museum to see where they thought major pain points were. We also spoke to the security guards who fielded directional questions daily. Key issues arouse quickly:

- The current signage system is not working. It is too minimal in quantity and too quiet in its design. Visitors do not see it when they need it.

- Transition spaces like elevators and stairs are not easily found through signage. “Where are the elevators?” is a question repeatedly asked.

- Washrooms are not easily found. “Where is the washroom?” is the number one visitor question.

- The Food Studio cafeteria is not easy to find. Restaurants are a big revenue generator for the museum and it needs to be found easily.

- The combination of the old and new architecture makes navigating to new galleries extremely disorienting and visitors feel frustrated.

Research

After hearing from the museum staff we spent days in the museum observing visitors. We immediately could see how confusing and disorienting the space was, especially for first time visitors.

An example of a typical journey would be: A visitor is searching for a gallery. They know what floor it’s on. They get directions from staff to an elevator. They get off the elevator in a cavernous white space and have little idea of which way to go next. They make it out of the elevator hall and look around confused. They pull out their map and consult with their friend. They can’t find where they are and then seek out another staff member for further directions. While the gallery they are looking for is around the corner, and it is incredible, their first feeling is frustration or annoyance.

Prototyping and Testing

Synthesizing this initial research we developed plans for temporary signage to quickly test potential improvements. When creating the signs we had to consider visitor pain points, areas where people were most disoriented or lost, major destinations, the multiple ways in which visitors could reach a destination and all the visual distractions they may encounter. We designed and installed 45 temporary signs on two levels of the museum.

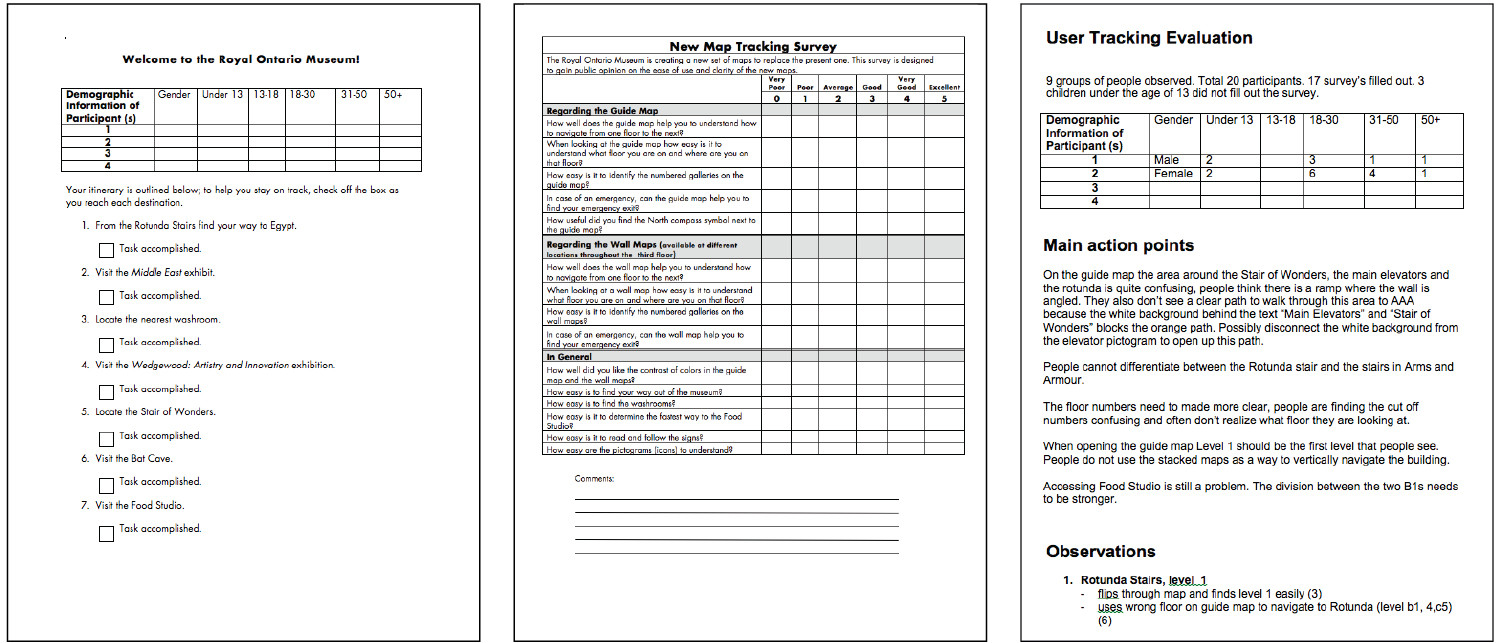

Once this signage was in place we created an online survey to find candidates to do in person observations. We created a visitor journey and asked participants to find galleries and places in the museum. We followed participants around and tracked their success. It was easy to identify when signage failed or worked by how quickly and easily they arrived at their destination. We rated the success of each sign and identified areas for improvement. See the full user tracking evaluation here. We then went back to designing solutions based on the unique characteristics of each location in the museum. We knew we were on the right track when staff noted that the number of questions they fielded in our test locations was down. Visitors were finding their destinations.

User research included interviews, surveys, observation, sign and map testing.

Testing and Prototyping Solutions

THE SOLUTION

The final proposal improved the visitor experience and addressed the key pain points:

- Improved signage visibility by moving to a high contrast black and white design on a matte surface. It allowed visitors to see the signs in the bright spaces of the new addition and amidst the collection. We also doubled the number of signs to address areas where visitor felt lost.

- Elevator and Stair locations were painted to highlight the areas on the white walls. Stair and elevators were also addressed with a new map treatment.

- Washrooms were given enlarged icons that could be seen from great distances. In some instances the icons were placed quite high so they could be seen above exhibition spaces.

- The Food Studio entrance on the main floor was painted, given more lighting and large signage so it could be viewed from the rotunda. It was also given extra attention in the map guide.

- The combination of the two buildings was the largest hurdle and we addressed this issue by adding exterior gallery signs to draw people forward from the transitional spaces. We also added more signs that addressed accessibility issues as the levels between the two buildings often transitioned with stairs or ramps.

- The content of each sign was carefully studied and tested to address where all types of visitors might want to go from that specific location to improve the visitor experience.

Our final proposal included six categories of signs: directories, identification, directional, safety, advisory and gallery signs. The signs were in both French and English and Braille when needed and included a new series of pictograms. Each sign had to be measured and placed in the space available. We created 405 signs in 15 standard sizes. We mapped these out for installation. The material for each signed varied according to type and installation location. Boards, vinyls, and pin letters were used. Sections of walls were painted to work with the scheme. This is a selection of signs from the final proposal.

Content was planned, tested and designed for

405 signs, directing visitors to 30 galleries on 7 floors of the ROM.

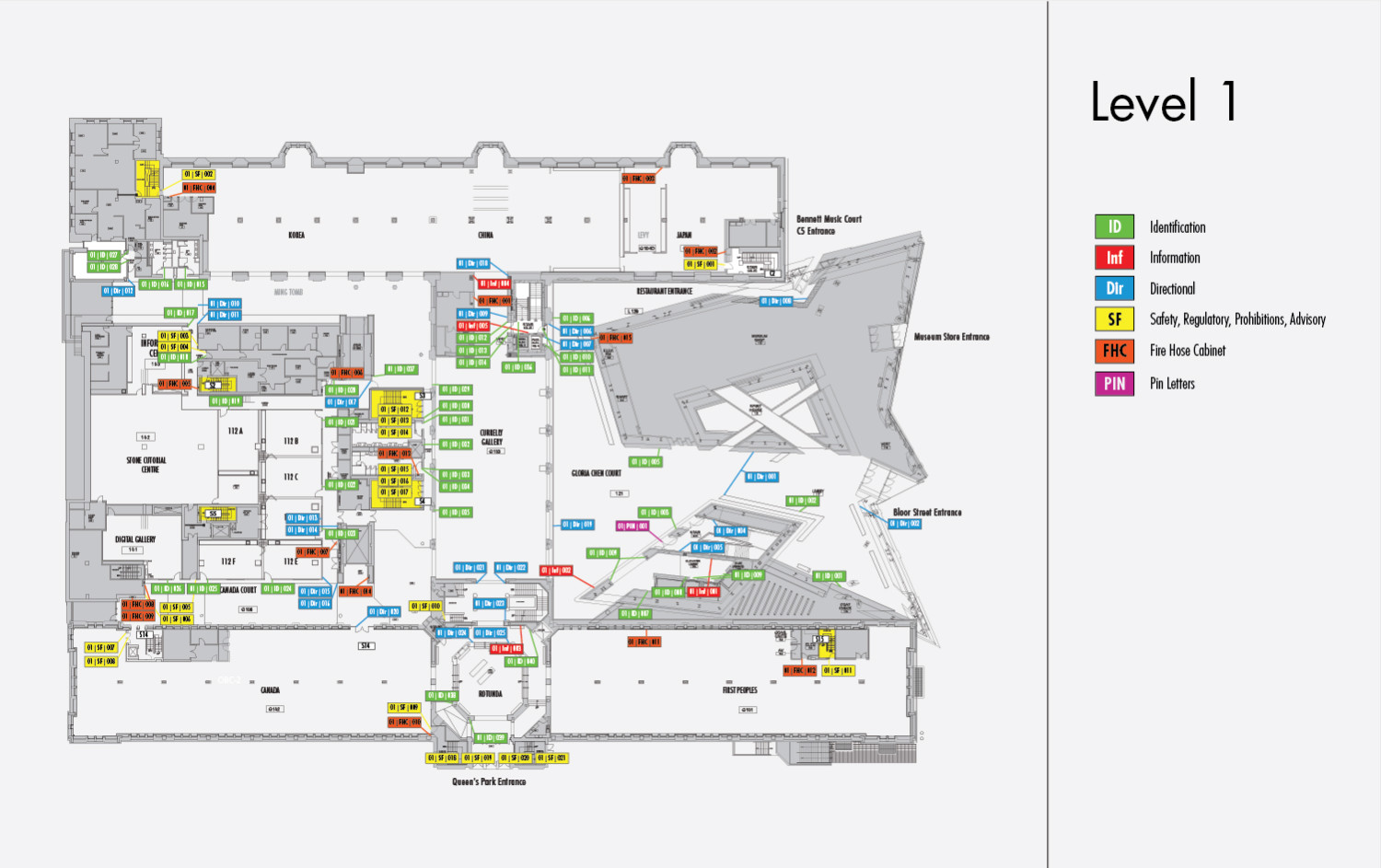

Installation Maps

The sign placement for each level was mapped for easy review and installation. Each sign was assigned a color-coded label and identification number.

Installation

Signs in major pain point areas were installed making it easier for visitors to navigate the museum and reducing the number of directional inquiries and lost visitors. The full project was put on hold due to funding being redirected.

I worked on smaller wayfinding projects under the supervision of the head of design that were fully implemented. These included wayfinding signage within the restaurant, signage for encouraging recycling and composting in the restaurant and large wayfinding graphics for the Diamonds exhibition.

How Does Wayfinding Relate to UX?

You might be wondering how the wayfinding process connects to the UX process. Matt Cooper-Wright of IDEO does a fantastic job of highlighting the connections in his article From Wayfinding to Interaction Design.

“Good UX and good wayfinding are the same in that when it works it fades into the background.”